Warning: Spoilers Are Present Throughout The Review

This year marks the 50th anniversary of one of the longest running franchises in the history of Hollywood: Planet of the Apes. Since the original film’s release, it spawned four sequels, two television series, a remake by Tim Burton, a critically acclaimed reboot trilogy and countless novels and comic books.

Since I’m a huge fan of the “Apes” movies, I’m going to look at the best and worst this franchise has to offer, starting with the 1968 original. Again, spoilers so please watch the film before reading. If you have seen it or don’t mind spoilers, read on.

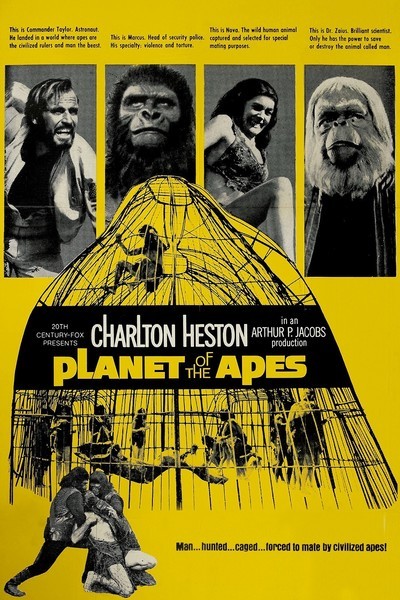

George Taylor(Charlton Heston) and other astronauts crash land on a mysterious planet, where apes speak and dominate the planet while humans are animals in the jungle.\

Script, Themes and Subtext

There is a lot to unpack with this movie. It isn’t simply a science fiction B movie with cheap thrills. This is the kind of science fiction I love to see, the kind that has something to say.

While captured, Taylor is hosed down, calling back to the tensions of the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s, where African Americans were hosed down by the police. The subject of race reappears in some of the sequels.

On my recent trip to the Museum of Natural History in New York City, I couldn’t help but think of Planet of the Apes while I walked the animal halls. Many of the displays are of real animals. Taxidermy is used in the original film, where Taylor stumbles in an ape museum only to find his dead comrade a stuffed model.

There are all sorts of human expressions used in Apes, altered to fit the ape world, as well as some fantastic dialogue.

- “Human see, human do.”

- “All men look alike to most apes.”

- “You did it. You cut up his brain, you bloody baboon!”

- “It’s a mad house! A MAD HOUSE!”

- “Take your stinking paws off me, you damned, dirty ape!”

In a clever bit of imagery, the orangutans perform “see no evil, hear no evil, speak no evil.”

The subtext of the film is worth noting, given its year of release. 1968 was a year in close proximity to great political turmoil. Unable to defend himself, Taylor’s one-sided trial scene reflects on McCarthyism and the government’s witch hunt of communists. The final script was written by Michael Wilson, who was blacklisted during the 1950s, giving the scene greater significance.

And of course there are the final moments. Taylor and Nova(Linda Harrison) ride off on the beach in the Forbidden Zone, despite Zaius’s warning, “You may not like what you find.” What does Taylor find? The ultimate symbol of America buried on the beach, and Taylor then realizes he’s been on Earth all along.

The film doesn’t blatantly say that humanity destroyed itself with nuclear weapons, but it is implied with the “Forbidden Zone.” Zaius reveals “the Forbidden Zone was once a paradise. Your breed made a desert of it, ages ago.” The world was still in the middle of the Cold War, where mutually assured destruction was a very real possibility.

The ending was a creation by Rod Serling, known for his shocking finales on his groundbreaking series The Twilight Zone. Boulle hated the ending, but it seems he was in the minority when it comes to the film’s ending, as it has been spoofed and referenced countless times.

Makeup, Music and Actors

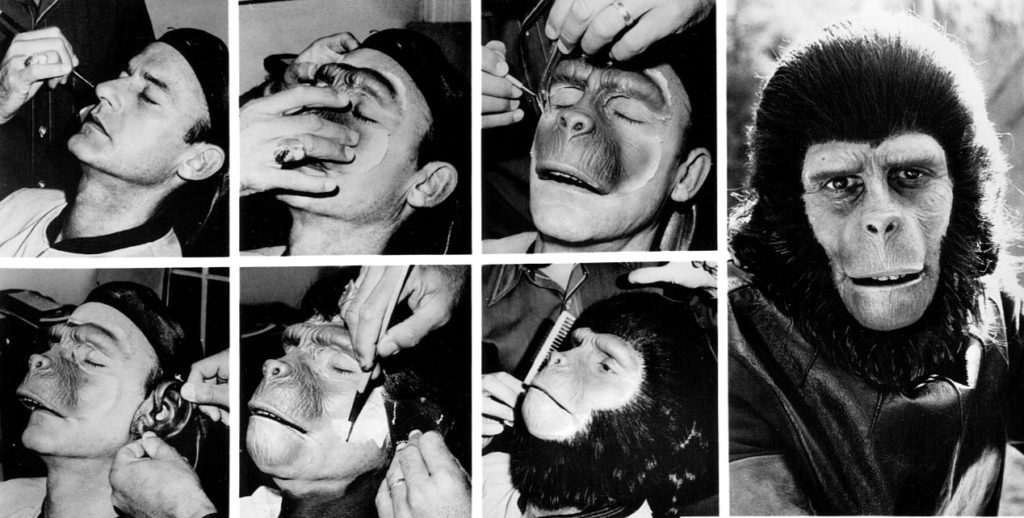

A script with great ideas and dialogue is good, but how do you bring the apes to life? The filmmakers were presented with a challenge of creating compelling ape characters the audience could take seriously. This is where John Chambers’ legendary makeup work has to be applauded. He won an Honorary Academy Award for his makeup achievement, and it certainly shows.

In older films, gorillas and other simians were special effects like in King Kong or men in gorilla suits. Of course this was decades before motion capture technology created compelling performances with more apelike appearances. While I’m impressed with the advances in digital technology, I am still in awe of Chambers’ work. His makeup allowed the actors eyes to show through, making the apes seem more human.

Attention must be paid to Jerry Goldsmith’s score, giving the whole situation an eerie feeling. From the first note you know something is off, especially with the way director Franklin J. Schaffner handles the trek through the Forbidden Zone and the chase scenes.

The worldbuilding in this movie is underappreciated. The apes have a sacred religious text as well as “the Lawgiver,” an ape who is their equivalent of Moses or Thomas Jefferson. The movie doesn’t waste much time in explaining the world, and it’s mostly Taylor questioning why the world is like this, and the exploration of the characters and themes.

Let’s not forget the stellar cast they assembled for this project. Charlton Heston, famous for biblical epics like The Ten Commandments turns in an excellent performance, creating a character that changes from cynic to a man filled with anguish and resentment. That final scene is a career highlight for Heston’s acting chops.

Kim Hunter as the curious and sympathetic Dr. Zira is simply a delight. Her cautious husband, Cornelius is played by Roddy McDowall, who is excellent. I’ll discuss McDowall more in my posts about the sequels. I have to mention Maurice Evans as Dr. Zaius. This guy is so despicable, concealing the truth behind mankind’s past accomplishments, as well as their downfall.

I think that’s what I like about the apes in this film. They may be out primate cousins but their motivations and personalities make them feel so human.

Conclusion

Fifty years later, Planet of the Apes is perhaps more relevant than ever. The fears of nuclear annihilation, the ‘other’ and the role of truth in the government ring true today as much as they did in 1968. Like the best Twilight Zone episodes, Planet of the Apes is a biting commentary on society, and it does this using the exotic trappings of science fiction. In this case, using some damned, dirty apes.

I hope you enjoyed this look back at the original Planet of the Apes. Next time we’ll take a look at its sequel, Beneath the Planet of the Apes.